Section

1 -

INTRODUCTION

|

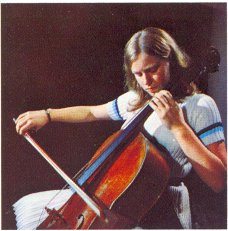

| Jacqueline du Pré

|

|

The release of the film, Hilary & Jackie, has created a fresh wave of interest

in the genius of Jacqueline du Pré. "Jackie", as she was called, was the greatest cellist of

her

generation, and many people consider her the finest interpreter of Elgar's Cello

Concerto. The film is based on the book A Genius in the Family by du

Pré's

sister Hilary and her brother Piers (Chatto & Windus, 1997). In the book's preface, the du

Prés

explain that it is not a biography: "These are our memories. This book is not a biography, nor

an account of Jackie's career. It is simply what happened. We offer the reader the story of

our family, from within."

Both book and film have caused a storm of controversy, with

some critics complaining about its "lack of objectivity". But the du Prés' intent was

to describe the Jackie they knew, not the world-famous musician. The public Jackie is

well-documented in another new book, Jacqueline du Pré (Weidenfield

&

Nicolson, 1998), written by Elizabeth Wilson with the assistance of du Pré's

husband,

Daniel Barenboim. A cellist herself, Wilson includes insightful comments about du

Pré's

recorded performances. Another excellent biography is Carol Easton's Jacqueline du

Pré (Hodder & Stoughton, 1989), currently out-of-print but well worth looking

for.

This biographical sketch draws on all three sources.

Section

2 -

STARTING AT

OXFORD

Jacqueline du Pré's parents met through the sheerest of circumstances. Her

father, Derek du Pré was a thirty-year-old London editor in 1938 London when

he won a trip to Poland. Staying in the town of Zakopane and knowing little Polish,

Derek asked if anyone there spoke English and was directed to woman at a nearby

villa. To his surprise, he discovered that the woman, twenty-four-year old Iris Geep,

was from Plymouth. She had come to Poland to study piano. Iris invited him in to hear

her play, and soon Derek was playing duets with her on his accordion.

The two were quickly attracted to each other and were married in London in 1940. Hilary,

their first child, was born two years later. In 1944, Derek du Pré, now serving in the

Coldstream Guards, was assigned a teaching post at Oxford. The family was living there, in

Beech Croft Road, when Jacqueline Mary du Pré was born on 26 January 1945. The

family lived in St Albans briefly after the war, then moved to Purley in Surrey when Piers

was born in 1948.

Their house in Purley was always full of music. Hilary remembers

that her mother was always singing and playing the piano, constantly turning music

into "wonderful games". The family was very close, Hilary and Jackie in particular.

They rarely had visits from the friends they made at school, preferring to play together

and create their own world of adventure. One day Jackie and her mother were listening

to a radio programme about the instruments of the orchestra. As the sound of the cello

filled the room, Jackie stood stock-still and listened with great attention. At the end,

she leapt up and said, "Mummy, I want to make that sound!"

On the eve of Jackie's fifth birthday, Iris tiptoed into Jackie's bedroom and left a three-quarter

size cello at the foot of her bed. Jackie made such rapid progress that the family

soon faced with a problem. Hilary was also a very talented musician. By the age of thirteen,

she would be invited to play a Bach piano concerto on television with the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra. Jackie's musical abilities started to create conflicts

between two sisters who had always been extraordinarily close. How Hilary and her

family came to grips with these tensions is one of the main themes of the book she and

Piers have written.

Section

3 -

CELLO

DADDY

When Jackie was eight, her mother decided she needed a more advanced teacher and chose

William Pleeth. Then thirty-eight, Pleeth taught at the Guildhall School and had been

a child prodigy himself. With his powerful, deep voice and what Easton calls a "thoroughly

un-English lack of inhibition", Bill Pleeth quickly became an important presence in Jackie's life.

She called him "my Cello Daddy". Pleeth later explained that teaching Jackie was "like hitting

a ball against a wall. The harder you hit it, the harder it would return. I could see the

potential quite strongly on the first day. As the next few lessons went on, it just sort of

unfolded itself like a flower, so that you knew that everything was possible."

In 1956 Pleeth recommended Jackie for the Suggia Gift, established by the great Portuguese

cellist Guilhermina Suggia and one of music's most prestigious scholarships. That

year's panel of judges was chaired by legendary conductor Sir John Barbirolli, who

was very impressed by Pleeth's recommendation. On the day of her audition for the

panel, he even helped Jackie tune her cello before taking a seat at the back of the hall.

A few minutes into her recital, Sir John leaned over to another famous member of the

committee, Lionel Tertis, and whispered, "This it! This is it!" One of the conditions of

the Suggia was that the winner practise four hours a day. At age eleven, Jackie

virtually left school and was cut off from normal school activities and relationships.

This, says Easton, "put Jackie irrevocably out of sync with her peers and ended any

semblance of a normal childhood."

Section

4 -

STUDIES WITH

CASALS AND

TORTELIER

Jackie played her first concert with an orchestra the next year, performing Edouard

Lalo's concerto with the Guildhall School Orchestra, conducted by Norman

Del Mar. At age twelve, Jackie "appeared to have no difficulties in presenting a full-scale

concerto with supreme confidence," Hilary recalls. In 1958 the du Prés moved to

London, taking a flat in Portland Place, near Regent's Park. Jackie continued studying with Bill

Pleeth, and one day he asked her to begin work on the Elgar Cello Concerto for their next lesson.

A week later, he was amazed to see that she had memorised the entire first movement. Elgar's

concerto had an immediate attraction for her, and it would become the work she

performed more than any other.

At fifteen Jackie became the youngest performer ever to win the Queen's Prize. Later that

year, she attended master classes with Pablo Casals in Switzerland. Now she was ready

for her professional début, and for the occasion, an anonymous benefactor bought her a

new cello: a beautiful 1673 Stradivarius. The concert took place in March of 1961, soon after

her sixteenth birthday, in Wigmore Hall, London. "I will never forget how deeply

moved I was by her that day", Hilary writes. "In that environment and with her beautiful

Strad, she seemed more impressive then ever! She and her cello were revealing

her true nature."

One year later, Jackie gave her first professional concert with an orchestra, playing the Elgar

Concerto with Rudolf Schwartz and the BBC Symphony Orchestra at

London's Royal Festival Hall. The Guardian's review hailed her as "the first cellist of

potential greatness to be born in England." That fall, Jackie studied with Paul Tortelier

in Paris, and played the Schumann concerto in London at Christmas time to more

superlative reviews. As she approached her eighteenth birthday, the musical world was at her feet

just as Jackie began wondering whether she wanted to continue to play the cello.

Section

5 -

TO THE

MOUNTAINTOP

For the next two years, Jackie went through a period of recurring self-doubt. "I was changing

from a child into an adult," she told Easton later, "and work took on a different aspect." She

stopped her lessons with Bill Pleeth and for a while refused most engagements. Realising how

little education she had had outside music, she studied maths and science with her friends. When

she did play the cello, she sometimes noticed a numbness in her fingers, but had no idea

what was causing it.

Late in 1964, the same person who had bought the Strad for Jackie's début offered

to buy her another - one of the world's great cellos, the Davidoff, named for a

previous owner, nineteenth-century Russian prodigy Carl Davidoff. Jackie tried it out

at the dealer's, and instantly fell in love with the instrument. On April of 1965 she used it to play

the Elgar with Sir John Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra. "The

combination of Barbirolli, Jackie, and the Davidoff," Hilary reports, "produced a performance of

unique power and haunting beauty."

Jackie then embarked on the first of her many tours of the United States. After her

performance of the Elgar at Carnegie Hall, one critic wrote, "We now have a youthful

genius from a country noted for its musical restraint, who is leading us back to a richer tradition

which admitted that music is the expression of emotion." On Jackie's return, Hilary

asked her what it had been like in America; to which Jackie, who loved jokes, the more

ribald the better, replied, "Well, fatty puff, I'm an angel - the papers said so - and I

had a standing ovulation for ten minutes!"

That August Jackie and Barbirolli recorded their interpretation of the Elgar concerto with the

London Symphony Orchestra. It was her first recording session with an orchestra, but the LSO's

leader, Hugh Maguire, who had seen many soloists, was bowled over by her performance. "When

I saw her play, and from only a few feet away, I was totally, TOTALLY knocked out! It was so

beautiful and so inspired and so magical, that I didn't speak to her. There was nothing one

could say." The recording was an immediate success and remains one of EMI's best-selling

records of all time.

Section

6 -

HALCYON

DAYS

Jackie's last lingering doubts about a career as a cellist were put to rest

by a period of study in Moscow with Mstislav Rostropovich just after her twenty-first

birthday. Like Bill Pleeth, Rostropovich concentrated on expression, rather than

technique. This was Jackie's tendency as well, but, when she saw it confirmed by this

great musician, of whom she was entirely in awe, she felt new confidence in her playing

and in herself. At Christmas, 1966, Jackie was invited to a party to play chamber music

with some friends and met Daniel Barenboim, the twenty-four-year-old Israeli

conductor and pianist. They played the Brahms F major Sonata together and spent

much of the evening talking. The next morning Jackie called her sister and said, "Hil,

I'm in love, I'm in love." The two saw each other as much as possible over the next few months,

despite their busy schedules, and in May they were married in Jerusalem.

The next three years were a time of triumph for them both, with tours that took them

throughout North America and Europe and frequent visits to the recording studio.

Christopher Nupen has caught the excitement of those days in his classic 1967

documentary, Jacqueline du Pré and the Elgar Cello Concerto, which

includes

a complete performance of Elgar's work with Barenboim conducting. (Another Nupen

film shows du Pré and Barenboim playing Schubert's Trout Quintet with

Itzhak

Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman and Zubin Mehta. Both are available on

video.) Elizabeth Wilson's book gives a detailed account of Jackie's concerts and recordings, but

one concert from 1968 stands out among many extraordinary ones.

The Soviet army had just invaded Czechoslovakia, and du Pré and Barenboim

announced that

they would play Dvorák's Cello Concerto at Royal Albert Hall to benefit Czech

refugees. That morning, the couple received death threats and were placed under police

protection, but they insisted on performing. Midway through the concerto, there was a loud

sound, and the orchestra ground suddenly to a halt. It was only a broken string on

Jackie's cello. The concert soon went on, and Jackie gave one of the most riveting

performances of her life. "The memory of Jackie's playing that afternoon," Hilary

writes, "has never left me."

Section

7 -

ECLIPSE

In the spring of 1971, Hilary got an anguished phone call from Jackie, who was on tour in

America. She was exhausted from years of travelling and desperately needed a rest. Two days

later she cancelled her engagements and returned to Britain. For most of the next year, she lived

in Ashmansworth, Hampshire with Hilary, her husband Christopher Finzi, son of

composer Gerald Finzi, and their four children. Jackie returned to the recording studio

with Barenboim in December. No one knew it, but these would be her final sessions in

the studio.

In 1972 she resumed her concert appearances, but the numbness in her

hands that she had first noticed eight years before grew steadily worse. Her doctors

believed that it was caused by stress. In February of 1973 Jackie flew to New York for

four performances of the Brahms Double Concerto with Pinchas Zukerman and

Leonard Bernstein. At rehearsal she needed help to open her cello case and could not

feel the strings with her fingers. She told Bernstein that she was unable to play.

"Don't be such a goose", he told her. "You're just nervous." Although she

managed three of the concerts, the third was a disaster. It was her last appearance as a

cellist.

Bernstein took her to a doctor in New York, but he too could find nothing

wrong with her. Jackie began to wonder if she were going mad. Only in October, after

a series of tests in London, was it determined that Jackie was suffering from multiple

sclerosis, a progressive disease of the central nervous system. The music world was

stunned by the news that she might never play again, but Jackie and her family clung to

the hope that the disease might progress slowly. They even thought she might recover,

as some MS patients do.

Hope persisted until May of 1975, when new tests at the Rockefeller Institute in New York

showed that her condition was worsening. For the first time, the full force of the tragedy struck

home for Jackie, for her family and for the public. Tributes poured in, including honorary degrees

and an OBE. Jackie decided to participate in music in the only way she could: as a teacher.

Confined to a wheelchair now, she gave master classes at the Guildhall School and even

conducted several of them on television, but, in a long and painful process, her health continued

to decline. She died in 1987, at the age of forty-two. In the words of her friend Christopher

Nupen, "The loss is still touching the hearts of people all over the world, because this great cellist

had ways of reaching the heart that are given to very, very few."

Section

8 -

LEGACY

Jacqueline du Pré left a rich legacy of recorded performances that are among the most

popular classical recordings ever made. They include the concertos of Haydn,

Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Dvorák and Elgar,

among others, and much chamber music, too, including works by Bach,

Couperin, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and de Falla. (The du

Prés' book contains a complete discography by Andrew Keener.)

Her most popular recordings have been those of the Elgar Cello Concerto, which

include four versions from her twelve-year career. The earliest is a 'live' performance with Sir

Malcolm Sargent from 1963 (Intaglio INCD 7351); the latest is a Philadelphia concert with a

Barenboim from 1970 (CBS/Sony MK 76529). The performance with Barenboim that

was filmed for Nupen's documentary in 1967 is also available now on videotape

(Teledec 2292-46240-3). Best of all, in the opinion of many, is her studio recording

with Barbirolli with 1965 (EMI CDC 5-55527-2). Du Pré conveys all of Elgar's

yearning, tenderness and defiant despair, and Barbirolli's accompaniment is almost

telepathic in its response to each fluctuation of tempo and tone colour. The Rough

Guide to Classical Music says, "Few cellists have penetrated the concerto's inner

recesses so deeply, or produced a performance of such burning intensity. This is the

place to begin any Elgar collection."

|