|

A Musical Tour of the Work

conducted by Frank Beck

|

One of Elgar's favourite

walks while writing Gerontius

was from his cottage,

Birchwood Lodge,

down this lane to

the village of Knightwick.

'The trees are singing

my music,' Elgar wrote.

"Or have I sung theirs?"

(Photograph by Ann Vernau)

|

|

"The poem has been soaking in my mind for at least eight years," Elgar told a

newspaper reporter during the summer of 1900, just weeks before the

première of The Dream of Gerontius in Birmingham.

Those eight years were crucial to Elgar's development as a composer. From 1892

to 1900 he wrote six large-scale works for voices, beginning with

The Black Knight in 1892 and including

King Olaf in 1896,

Caractacus in 1898 and

Sea Pictures in 1899. He also conducted the

premières of each one, gaining valuable experience in the practical side of

vocal music. Most importantly, perhaps, he gained confidence, particularly after the

great success of the Enigma Variations in

1899 made him a national figure.

At forty-two, Elgar had waited long for recognition, and he now felt able to take

on a subject that offered an imaginative scope far beyond anything he had done before:

Cardinal Newman's famous poem of spiritual discovery. Elgar set slightly less than half

of the poem, cutting whole sections and shortening others to focus on its central

narrative: the story of a man's death and his soul's journey into the next world.

Part 1

Gerontius is written for tenor, mezzo-soprano, bass, chorus and orchestra. The

work opens with a somber melody in D-minor marked pianissimo. This was named the

Judgement theme by Elgar's friend and publisher August Jaeger, who wrote a

detailed analysis of the score. The opening subject launches an orchestral Prelude that

presents all of the work's main themes. They are some of Elgar's most fertile melodic ideas,

dovetailed here so that one flows seamlessly into the next. When the theme arrives that will

accompany Gerontius's anguished prayer in Part 1, the music builds to an urgent climax with

organ accompaniment and pounding timpani. A march-like theme brings us to a brief reprise

of some of the several earlier subjects, leading directly into the tenor's first solo.

Elgar developed a unique vocal style for Gerontius, neither simple recitative nor

full singing, but one that allows the music to shape itself to the words in a natural and

expressive way, and we can hear it in the first line, 'Jesu, Maria, I am near to

death ... .' This treatment can modulate easily into song, as it does here on the very

next line, 'And thou are calling me.' Elgar's sketches show that he went through draft

after draft to achieve this kind of flexibility throughout the work, partly so that the

vocal line could respond to the poem's sudden shifts of mood: in these eighteen

opening lines Gerontius goes through feelings of desperation, terror, supplication and

then exhausted calm.

Now the friends at Gerontius's bedside pray for him with a 'Kyrie eleison' ('Lord

have mercy') that begins in the semi-chorus without accompaniment. At the rehearsals

for the first performance, Elgar urged the chorus not to sing as though they were in

church, but with 'more tears in their voices,' as though they were at the side of a dying

friend. His friends' prayers rouse Gerontius to a more spirited solo, followed by a

second choral section, 'Be merciful, be gracious,' in the form of a subdued fugue.

|

|

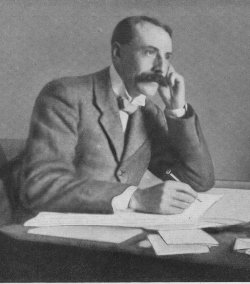

"I cycled over from Ledbury to lunch with him ... he was greatly relieved

at having that instant written his name under the score of the last bar [of

Gerontius] ... I begged Elgar to remain just as he was while I went down and

fetched my camera."

- William Eller, 3 August 1900

|

|

The music then shifts into 3/4 time for 'Sanctus fortis', Gerontius's dramatic

statement of faith. It is a passionate declaration, not a pious one - the final 'Sanctus

fortis' is marked piangendo ('wailingly'). "I imagined Gerontius to be a man like us,"

Elgar told Jaeger. "Not a priest or a saint, but a sinner ... no end of a worldly man in his

life, & now brought to book. Therefore I've not filled his part with Church tunes &

rubbish but a good, healthy, full-blooded romantic, remembered worldliness."

The chorus sings 'Rescure him, O Lord,' and then we hear the last earthly words of

Gerontius, 'Novissima hora est,' ('It is the final hour'). With only a brief pause, the

Priest, sung by the bass, gives Gerontius his blessing: 'Proficiscere, anima Christiana,

de hoc mundo' ('Go forth from this world, Christian soul'). Elgar's melody here

conveys faith, sorrow and wonder, all at once, in one of the work's most inspired

passages.

At the words 'Go in the name of Angels and Archangels,' the chorus joins in,

building to a triple forte on the words 'go forth.' The Priest sings a second benediction,

the accompaniment softens to a single melody for the first violins, and then one last,

gentle swell of orchestra and voices on the words 'through Christ our Lord' brings the

movement to an end in D-major.

Part 2

A delicate, new melody in F-major and 3/4 time marked dolce e legato ('sweet and

smooth') conveys the 'inexpressive lightness' felt by Gerontius's soul after death. When

his soul begins to sing 'I went to sleep; and now I am refreshed,' the feverishness of his

death is gone, and all is deep calm. The time signature is significant: much of Part 2 is

in triple time, giving the music a greater lightness than the quarter time rhythms that

predominate in Part 1.

Gerontius's soul soon realises that he is not alone; he hears an Angel singing 'a

heart-subduing melody.' In Newman's poem, the Angel is male, but Elgar gives the role

to a mezzo-soprano. Her first solo is magical, creating a feeling of exhultation with the

simplest musical means: listen to how the near-recitative of the first five lines lifts into

song for a resonant 'Alleluia'.

Now comes one of the work's most memorable passages, as the soul and the

Angel converse and the musical setting interprets the words with great imagination.

The soul is hesitant, but curious to know 'a maze of things' about his new condition.

The Angel's response is understanding and compassionate: 'You cannot now/Cherish a

wish which ought not to be wished.' Their dialogue leads into a radiant duet, the Angel

reassuring the soul about his fate, the soul singing of his new-found joy.

But dangers are still lurking: Gerontius's soul hears demons singing a fierce,

mocking fugue, intensified by cries of sarcastic laughter. As the demons pass, the soul

notices that he has only heard them, not seen them. Will he be able to see God? The

Angel says he will, but warns that 'the flame of the Everlasting Love/Doth burn ere it

transform.'

|

|

The first performance of Gerontius, on 3 October 1900, was conducted

by the legendary Hans Richter at Birmingham Town Hall as part of the Birmingham

Festival.

|

|

The soul hears distant singing, the first sounds of a choir singing 'Praise to the

Holiest in the height.' The Angel announces that they 'have passed the gate, and are

within/The House of Judgement' The pace quickens, and the surging music reminds

Gerontius of 'the summer wind--among the lofty pines.' There is a great, expectant

moment as the Angel sings, ecstatically, 'And now the threshold, as we traverse

it,/Utters aloud its glad responsive chant.'

And then all the voices join together triple-forte, singing 'Praise to the Holiest' with

thrilling support from the orchestra. This is the beginning of one of the most elaborate

and stirring passages in choral music : Elgar called it 'the great Blaze.' The music

swings into a second subject in 6/4 time on the words 'O loving wisdom of our God!'

and the two subjects blossom and intertwine in soaring four- and eight-part harmonies.

As a boy, Elgar lived just down the street from Worcester Cathedral and spent many

happy hours listening to the music there. Later he learned the choral works of Bach,

Handel, Mendelssohn, Brahms and Dvorak by playing violin in the Three Choirs

festivals. His knowledge of cathedral acoustics and of choral writing are apparent

throughout this delightfully intricate song of praise. When the hymn's refrain is sung

for the last time, voices and orchestra recombine in C-major for a final, echoing

chord.

A brief orchestral passage leads to the Judgement scene. The Angel of the Agony,

a second part for the bass, pleads with Jesus to 'spare these souls which are do dear to

Thee.' We then hear the voices on earth praying at Gerontius's bedside, suggesting that

all the events of Part 2 have happened in an instant of time. The Angel sings a last

'Alleulia,' and the Judgement theme builds throughout the orchestra, rising to an

enormous crescendo. The score says, 'For one moment, must every instrument exert its

fullest force.'

The sight of God is overwhelming: the soul sings 'Take me away,' drawing

together many earlier themes, and the Souls in Purgatory sing the psalm, 'Lord, Thou

has been our refuge'. Now comes the great song of compassion that crowns the work,

the Angel's 'Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul,' with loving counterpoint from

the chorus and semi-chorus. There is an echo of 'Praise to the Holiest' and of the

psalm, and then, with a rapid diminuendo, the repeated 'Amen' moves into D-major to

bring this wonderful work softly and serenely to a close.

|